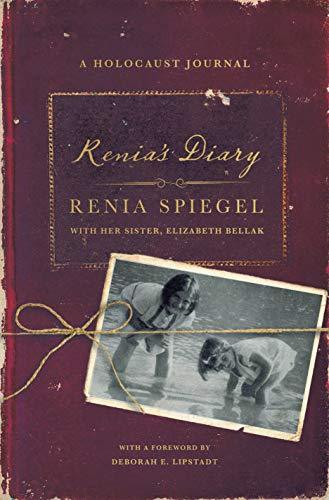

Narrating Renia’s Diary

November 2019: I’ve been reading articles published with increasing frequency across media outlets such as The New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, and more, about “the Polish Anne Frank”. The headlines read “Before there was Anne Frank, there was Renia Spiegel”. It sends chills down my spine and my eyes fill with tears, because I feel I know Renia.

MacMillan Audio reached out to me earlier this year, asking me to audition for a diary narration project. It was Renia’s, having been dug out of a bank vault, where it had lain dormant for over 70 years, and was now headed to print and audio. I was honored to be asked to audition, and hoped fervently that I did a good job, because memoirs and texts such as this are my favorite to narrate. I also feel strongly that these particular stories need to be told, and what a profound honor it would be to win the audition.

I was quickly notified that I won the project, and then trepidation set in. The amount of Polish, German and even Russian words was exhaustive. MacMillan sent me brilliant audio recordings of a native Polish speaker pronouncing most of them, but I still had three pages of words that I had found on my own. So I reached out to a local Polish school and arranged to meet with a lovely woman, Karolina Mancino, in a nearby library, to record the rest.

I also had concerns about recording conditions in my home studio. We were renovating our kitchen and in order to have the pristine, silent recording environment needed, I chose to record at night. It was a surreal experience, and put me, mentally and emotionally, in Poland during this time period. I imagined Renia, sitting in the darkness of her grandparent’s upstairs bedroom, carefully recording in her beloved diary, all the ups and downs of her daily life. I felt as if I were physically sitting on the edge of her bed, watching her write, and continued sitting there, every night, entry after entry, through 700 pages, as she wrote. I wanted to hold her by the shoulders, peer into her eyes, and tell her earnestly, urgently “Go. Cross the bridge into Warsaw and be with your mother. Find a way to make it happen. YOU. MUST. GO.” She actually did go, but then returned, presumably to attend school. The initial entry on January 31, 1939, at the age of 14:

“Today, my dear Diary, is the beginning of our deep friendship. Who knows how long it will last? It might even continue until the end of our lives. In any case I promise to always be honest with you, I’ll be open and I’ll tell you everything. In return you’ll listen to my thoughts and my concerns, but never ever will you reveal them to anybody else, you’ll remain silent like an enchanted book, locked up with an enchanted key and hidden in an enchanted castle. You won’t betray me, if anything it’ll be those small blue letters that people are able to recognize.”

Night after night I was an unseen observer in her world, as she navigated the murky, often turbulent waters of relationships with her grandparents, her little sister, Ariana (now known as Elizabeth Bellak), her schoolmates, and her first love, Zygmunt. She mourns her mother incessantly, and describes with love and exuberance, the way spring felt in her town of Przemyśl. But each entry has a current of grief, longing, and fear running through it.

“Now I live in Przemyśl, at my granny’s house. But the truth is I have no real home. That’s why sometimes I get so sad that I have to cry. I cry, though I don’t miss anything, not the dresses, not sweets, not my strange and precious dreams. I only miss my Mama and her warm heart. I miss the house where we all lived together, like in the white manor house on the Dniester River.”

And scattered throughout her entries, are poems she wrote. Her writing was cherished by those who were close to her, and recognized with honors in her classes at school. She seemed to find it easier to pour out her heartaches, observances and angst in poetry, than in her regular journaling.

“The moon swims out in silence

To shine in the sky, to shimmer for dreamers

While below a street rumbles shrilly

Crunching with labor, hot and weary

Loud rat- tat- tat- tat of human steps

Echoes from cobbled streets

Gray carts and their wheels

Groan and never miss a beat

Taxis whoosh ahead

And red tramways smoothly slide

On their tracks of steel

Stopping only sometimes

To take in yet again

Another mass of people

Then leave without complaint…”

As the pages continued, her observances grew more dire. Rail carloads of people were collected and shipped off to concentration camps. She recounts the day she was forced to wear a yellow Star of David on her clothing to designate her as Jewish, and she struggled with what it meant to her. In the Foreword, Deborah E. Lipstadt, Dorot Professor of Holocaust History at Emory University writes: “Was wearing it an act of compliance with a hateful regime or did it demonstrate a pride in one’s Jewish identity? We read of her reactions to passersbys’ comments. Some express solidarity and others pity. She reflects on them, not from a distance of many years, but on the day she encountered them.”

Each night, after turning off the lights, closing the door to my recording booth and crawling into bed in the early hours of morning, I found sleep elusive, my mind whirling in a sympathetic depression and anxiety, reexamining Renia’s life, word by word.

At the conclusion of the diary came the last entry, written by her boyfriend, Zygmunt. He had hidden Renia and his parents in an attic of an acquaintance in the ghetto, in an effort to save their lives. Their presence was leaked to the Nazis, and she was shot in the nape of the neck on the street, in front of him.

“JULY 31, 1942 Three shots! Three lives lost! It happened last night at 10:30 p.m. Fate decided to take my dearest ones away from me. My life is over. All I can hear are shots, shots . . . shots. My dearest Renusia, the last chapter of your diary is complete.”

Despite having read this entry more than once as I prepared the text for narration, I had to leave the booth. Overcome by emotion, I sat in my bathroom and sobbed uncontrollably as the senseless, evil loss of life of an unimaginable number of people washed over me. It took me a long time to achieve composure and clear quality of voice, to continue narrating the Afterword and Notes Renia’s sister, Elizabeth Bellak, had written.

Renia’s niece, Alexandra Bellak, together with her mother, Elizabeth, filmmaker Tomasz Magierski and a team of translators, worked hard to bring this diary to life, after it sat dormant locked in a safe deposit box for decades. Renia’s Diary and other holocaust accounts I’ve narrated have shown me that evil like this can and will happen again, probably in my lifetime. These accounts are sacred and need to be shared far and wide. As difficult as they can be to give voice to, and I will not turn down these projects if they come my way. Their voices need to be heard.

Thank you, Renia.